You don’t need an editor! You don’t need anyone!

—The Worst Muse

I didn’t think we needed that “intrusion” on a creator’s work, and the reason for this was how many horror stories have we all heard from somebody that’s working for DC, or whoever… I didn’t want an editor saying, “Jeez, Dave McKean, I really hate that scene on page 24 of Cages #3, where you have this character saying, “Blah, blah, blah … You’ve really got to change that, or I’m not going to let it go through.” That’s what I perceive as an editor. And I don’t agree with that.

—Kevin Eastman, “The Kevin Eastman Interview, Part 2” by Gary Groth, The Comics Journal #202 (originally published March 1998)

The first quote, in case you’re unaware, is a joke. The Worst Muse is a Twitter account dedicated to being the voice in every bad writer’s head, providing the most god-awful tropes and notions that could ever pop into his or her head—and have, more often than not, been carried all the way through to the finished project.

The second quote, unfortunately, is not.

These days, most comic and pop-culture fans know Kevin Eastman solely as co-creator (with Peter Laird) of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the prime example of the little small-press comic that could (and still does!). But in 1990, Eastman—who’d struck gold in the ’80s with TMNT—decided to use a good portion of his Scrooge McDuck–sized fortune to bankroll a new venture: Tundra Publishing. It was intended to be the home of high-end comic projects that mainstream houses like Marvel and DC wouldn’t have even thought of considering, and for a while it succeeded: Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s massive (and massively acclaimed) Jack the Ripper graphic novel, From Hell, got its start there, as did projects like Scott McCloud’s nonfiction analysis Understanding Comics and Mike Allred’s frenetic superhero spoof Madman Adventures.

Tundra closed in 1993.

A lot of it had to do with poor management: accepting too many projects; royalty splits of 80% for the creator and 20% for Tundra (after costs); creators getting paid but not delivering their work; Eastman’s refusal to listen to advice on how to run the business—even when it came from Doubleday’s Ian Ballantine, one of the demi-gods of publishing; paying an artist $20,000 for his work, then finding out he tore the pages to shreds in a fit of anger. By the end of its run, Tundra had become a $14 million money pit, and Eastman had to shut its doors.

But Tundra also suffered from a lack of editorial control—Tundra hired production people as traffic managers (called “straw bosses”), to make sure that projects got from point A to point B, but they were to remain hands-off when it came to the actual content of those projects. Tundra was all about the creator’s “vision.” Because it was believed that editors as a whole are a terrible bunch of hacks—failed writers who try to prove their worth by pissing on the visions of the creators they work with, just to prove they’re superior storytellers.

Riiiight.

Now, I’m not saying there aren’t editors in the world who like to “mark their territory” just to prove who’s the boss, because there certainly are. Or, conversely, that there aren’t editors who’d rather be chummy with and starstruck by the talent instead of acting as a helping hand, especially when it comes to big-name authors and artists—because God knows I’ve met some; they’re the ones who usually say, “I can’t edit him (or her)! He’s (or She’s) _____!” Or that there aren’t editors who lack vision—sometimes for absolutely baffling reasons. (I’ll give you an example of that sort of madness another time.)

But those are the exceptions, not the rule. A good editor isn’t there to destroy the work or be your suck-up buddy, they’re there to offer advice, to tell you where the writing is weakest (and where it excels), to point out structural issues and offer suggestions, and, when necessary, to tell you when you’re hurting your creation with your terrible writing. And they’ll tell you all of this because they want you to succeed.

Really.

And it’s something that even Kevin Eastman probably came to learn in the post-Tundra years—after all, he’s recently returned to writing and drawing TMNT stories for comic publisher IDW, and has to deal with editors there. And long before that, back in 1999, Kevin and I got along just fine when I was the ibooks, inc. editor who handled Heavy Metal: F.A.K.K.2, the novelization of the Eastman-produced animated feature Heavy Metal 2000—the one major problem with the project being that the book came out a year before the movie, and then the movie was released under its own title, which killed the book’s tie-in sales. Still, Kevin and I got along so well that he had no problem in later approving me as the author for the TMNT novel trilogy that ultimately never came to fruition.

So yes, when an editor knows what they’re doing, they can be your staunchest ally, and your most enthusiastic supporter, when it comes to getting things done right. But they can also be your harshest critic, because they know you can do better. And if you’re willing to listen to their feedback, you will do better.

Which brings us to the editorial tale of a little book called Blood Feud: The Saga of Pandora Zwieback, Book 1…

Howard Zimmerman (l.) and me at the 2010 New York Comic Con.

“So where’s the girl in the comic?”

That was the first question my friend and editor Howard Zimmerman (whom longtime sci-fi and comics fans may recognize as the former editor-in-chief of Starlog, Comics Scene, and Future Life magazines) asked me back in 2010 when we sat down to discuss his edits on the manuscript for Blood Feud, the first Pandora Zwieback novel. I didn’t know what he was talking about.

He pointed to the print copy of The Saga of Pandora Zwieback #0—the free introductory comic I’d been handing out to convention-goers in the year leading up to Blood Feud’s publication—on his table. “Well, the girl in this comic is happy and funny and likable, and the girl in this”—he pointed to the manuscript—“isn’t. So where is she?”

“Well, the comic takes place after the novel, so she’s different,” I said—knowing even as I said it how stupid it sounded.

In fact, Howard continued, the book was filled with unlikable people—from Pan to her parents, even to Annie. Karen and Dave hated and sniped at one another throughout the book; Dave was months behind on child support and alimony—but had still found enough cash to pay for a vampire skeleton to ship from England (Howard referred to him as the “biggest dick” he’d ever read about in recent months); Annie was putting the moves on Dave; and Pan was sullen and argumentative and hated damn near everybody. It was an angry book about angry people, and he was pretty sure that’s not what I’d set out to write.

So I did what any author usually does when somebody beats the hell out of their work and questions their skills (I used to edit for a living and I handed out a lot of beatings, so I know): I got my back up. I defended the writing, nodded politely as Howard tried to tell me where stuff needed improving, and then headed home, convinced he just didn’t understand what I’d written.

A couple days later, I reluctantly sat down and started reading his edits:

Pandora is the most realized character, but she has too many airhead moments, which not only keep the story from getting too serious, they also keep readers from taking Pan too seriously. Teenage angst is hormonally driven; fear of being ostracized is enough for teens to commit suicide. Pan should be a “haunted” character. She has had “monster vision” for years. She has been treated as though they are hallucinations and put on medication, so clearly she either thinks she is insane or that she is being totally mistreated. Either state of mind would give the character an edge currently lacking. Or, rather, mostly just seen when she punches out her rival in the mall. That’s a good beginning, but should be just the top of the iceberg.

Dave is a two-dimensional slapstick character who we suddenly have to take seriously toward the end of the book. It’s very easy to see why Pan’s mom divorced him. He comes across as totally incompetent. It’s amazing he can keep his business running and the store open.

The final few chapters seem to be different in intent from the balance of the draft. They are leaner; harder. It’s almost as though THIS is the voice you need for the book, but have only discovered it toward the end of telling the story.

There were a lot more comments along those lines, as well as a plea to cut down the manuscript—the first draft was close to 500 pages—and suddenly I realized he was absolutely right. About everything. Pan wasn’t complete as a character. Dave was an asshole. About the only likable characters in the entire book were the friggin’ vampires. And holy crap, where’d all the anger come from?!

And yet…there was still a story in there among the confrontations. A story about a girl who’d been treated like an oddity most of her life; who was brimming over with pain and wanted it to end; who needed to know how special she really was. If I could get past the anger and the shouting I could find that story.

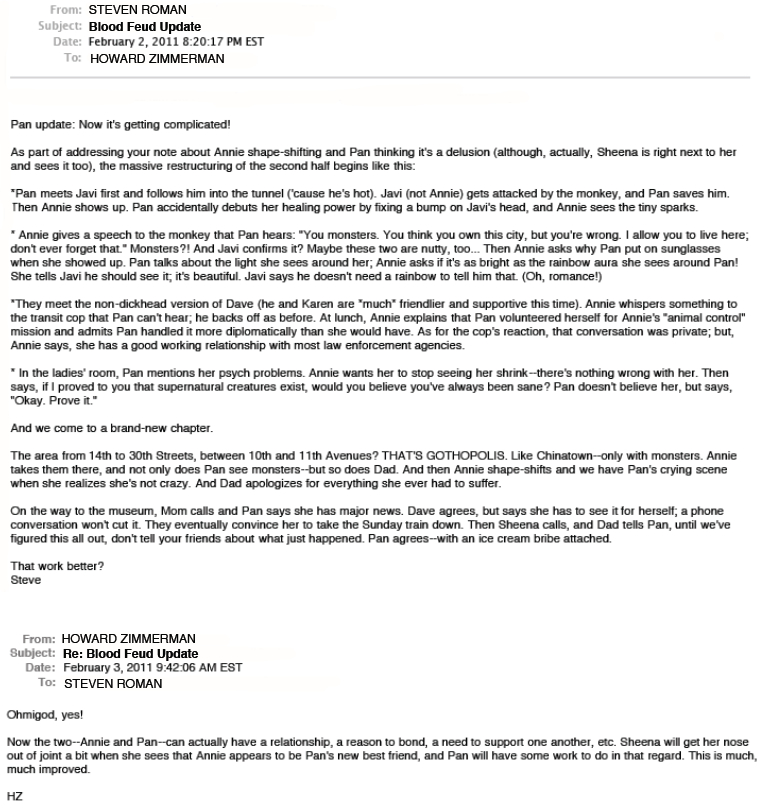

I started digging, and much to my surprise, it didn’t take as much effort as I’d expected, as I explained to Howard about a week later (click to embiggen, as they say):

See, a writer is allowed, even expected, to get defensive about their work—it’s perfectly understandable and part of the game. But a smart writer then puts aside the defensiveness and listens. Unlike what Kevin Eastman believed, back in 1990, or what a lot of authors may still believe—that an editor is just there to pee on the writer’s work and screw with their “grand vision” (which, truthfully, is what a bad editor may do)—the bottom line is (to be blunt about it): your shit ain’t gold. The words aren’t written in stone. Or, as award-winning producer/showrunner Steven Moffat often points out in his scripts for Doctor Who, time can be rewritten. So can your prose.

(For example: An author once responded to my work on his short story by bellowing, “There was more editing in that one story than in my last ten novels!” My response? “Well, what does that say about your last ten novels?” Then his head exploded. 😀 But he listened to my comments and agreed they made sense, and the story got published with most of them taken into consideration.)

When they do get their asses kicked by an editor, writers shouldn’t always fall back on friends and family (or their own ego) for a counterargument—most of the time they’re just enabling your bad writing by telling you how wonderful it is, that others don’t understand your “genius.” Howard might be my friend, but before that he was an editor for over thirty years (not to mention my boss when I started out in book publishing as his assistant editor, in 1994), and an editor who cares about improving the work is worth their weight in ego-stroking well-wishers. The good editors fight you (sometimes) because they want you to tell the best story possible, to help you grow as a writer. And after you’ve cooled off, 9 times out of 10 you’ll agree with them; maybe not 100%, but enough to see where they made a good point about some element that you really do need to change.

In my case, agreeing with Howard’s feedback meant I’d be rewriting half the novel. Still, now that he liked the new direction I’d proposed, I knew I was on the right track for the second draft.

Tomorrow, I’ll tell you about the chapter that, for me, became the linchpin for the entire revised novel—a chapter that didn’t exist in the first draft.