Even with the usefulness of the Internet, it’s sometimes difficult to keep up with events in the publishing industry. Which is why it came as such a surprise last week when I learned of the passing of Michael Z. Hobson on November 12, 2020, at age 83 due to heart failure. (The fact that the sad news broke over Thanksgiving Day weekend probably had a lot to do with that announcement being overlooked.)

Mike had been a Harvard graduate, a literary agent, and an executive at Little, Brown and Company and Scholastic Publishing before joining Marvel Comics as an executive vice president from 1981 to 1994.

He was also Pandora Zwieback’s first advocate.

As I often say, get comfortable—it’s a lengthy tale…

Our association started in 1997, during my time as a book editor, when my boss at the time, Byron Preiss, had hired Mike to be executive vice president of publishing for Byron Preiss Multimedia Company, which not only produced screensavers and the like but also co-published a highly successful line of original novels and anthologies based on the Marvel Comics characters (my three X-Men: The Chaos Engine novels, published from 2000 to 2002, were part of that line). It didn’t taken Mike very long, however, to discover that as EVP he wasn’t really allowed to make a lot of final decisions; as president and publisher, Byron held on to that position. Over time, Mike grew tired of the situation and decided to move on—the line of wellwishers on his last day stretched down the hall.

But in the time he was at BPMC, we’d gotten to be friendly. Mike was an easily likeable guy: he didn’t put on the sort of superior attitude you’d expect from someone who’d been in the business as long as he had, and who’d been a top-level executive for just as long. He was attentive, encouraging, and a firm believer in letting creative people be creative.

It was those qualities that made him one of the most respected people in publishing; adding Mike to your roster was considered a major get. So it was no surprise that after he departed BPMC there was news in 1998 that he’d landed as the new president of Parachute Properties, whose book-packaging company, Parachute Publishing, was the home of R.L. Stein’s bestselling Goosebumps and Fear Street series (also books starring the Olsen Twins, but…meh).

That summer, after he’d had time to settle in at the new place, I got a call from Mike, and an invitation to lunch. Hey, who was I to turn down a free meal?

At a bistro not far from Parachute’s offices, Mike explained the reason for the get-together: he was looking for new titles. As he put it, he’d sat down with management and told them that Goosebumps and Fear Street were all well and good, but if Parachute was to remain successful, it needed to expand its lineup, and that meant bringing in outside projects—creator-owned outside projects.

That was a huge step. Book-packaging companies like Parachute—as well as Byron’s Byron Preiss Visual Publications—typically owned the projects they assembled, and hired authors and artists through work-for-hire contracts, which meant that what they wrote and drew was wholly owned by the company. For a packaging company to start offering deals in which they were profit participants on projects but owned no part of them would be a game changer.

Mike went on to remind me that he greatly enjoyed my writing and my approach to editing, which was why, given the praise he’d just heaped on me, I thought he might be headhunting me to join him as a Parachute editor. But he had an even better proposal to offer:

“So…do you have any project of your own you think would fit in at Parachute?”

Well, no, but that didn’t mean I wouldn’t have one for him in record time!

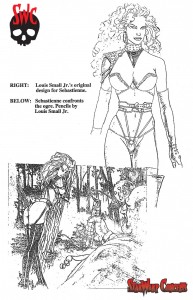

A couple weeks later I presented him with Heartstopper, a proposed six-book series of young-adult novels starring an immortal monster hunter named Sebastienne Mazarin and her teenaged Goth-girl sidekick, Pandora Zwieback. I even included character designs, courtesy of Pan and Annie’s co-creator, artist Uriel Caton, who had collaborated with me on the original-but-failed Heartstopper mature-readers comic published in 1994. (Hey, there’s nothing wrong with recycling a title and a character and adding a teen assistant to get it into the YA market.)

Mike loved it. He loved the title—Heartstopper was a short, memorable title like Goosebumps, easy to sell. Even more, he immediately saw its potential—not just YA books, but comics, movies, TV shows, merchandising…yes, this was exactly the sort of new Parachute title he was looking for. By mid-1999, after some fine-tuning of the proposal and a series of editorial back-and-forths, a deal was reached and contracts signed—Heartstopper was now one of the half-dozen (or so) creator-owned properties that Parachute Publishing was going to package. Even better, Mike had put me in touch with one of the other property owners, an artist who needed a writer to help develop his storyline; so now I was looking at two writing projects!

“Off we go!” Mike wrote in his cover letter to the final executed agreement.

But then a few months later I got another call from Mike, and another invitation to lunch. When we got together, Mike explained he had some very bad news to deliver: the new line of books was being scuttled. He couldn’t tell me exactly why that was—that was in-house politics not open for discussion with outsiders—but my impression was that Parachute soured on the idea that they weren’t going to own any of these new properties and thereby reap all the benefits. And possibly they hadn’t realized at the start just how successful Mike would be in launching his plans, or how quickly he’d be able to line up talent for them.

So now they were killing the program, and Mike was placed in the position of having to go back to all us creators and apologize for having us do all this work for no reward. (Since we owned the properties, none of the creators were paid for developing them; the money would have come from eventual sales and a 50/50 split with Parachute. But we all understood that going in.)

For someone with Mike’s standing in the industry, it was a major embarrassment.

The good news, though, was that with the publishing deals dead the creators were free and clear to do what we liked with our projects, hopefully finding homes for them at other publishing houses. Mike even later reached out to some of his contacts to see if Heartstopper could land somewhere (unfortunately, everyone passed on it).

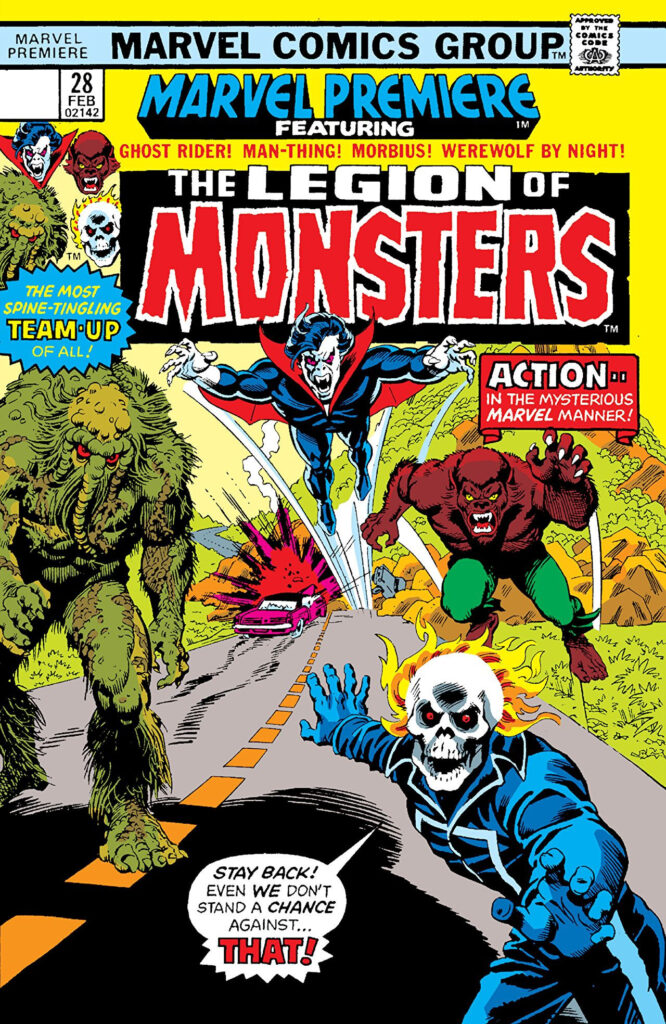

After that, I’d occasionally run into Mike at trade shows like Book Expo America, although in 2000 he went above and beyond just hoping I’d become successful as a writer and editor by convincing Marvel Comics’ licensing division to make me an unusual offer: If I was interested, they’d hand me the publishing rights to all their supernatural characters—which Byron had turned down because he disliked horror—in order to create my own line of original novels and anthologies.

Doctor Strange, Blade, Dracula, Ghost Rider, Man-Thing, Werewolf by Night, Satana the Devil’s Daughter, Morbius the Living Vampire, even the superheroic mercenary Moon Knight—all those and more, mine for the taking because Mike had such confidence in me. Of course I was interested, but things just didn’t work out, unfortunately. That’s a story for another time, though.

By 2003, Mike had retired to become a part-time consultant in publishing, but every time we met he’d ask if anything was happening with that Heartstopper thing. Over time I let him know that the title had changed to The Saga of Pandora Zwieback—the teen-girl sidekick having shifted to the lead position—and he’d encourage me to keep at it.

The last time I saw Mike was in 2011. Elated over the fact that I’d finally taken the plunge and self-published the first Pandora Zwieback novel, Blood Feud, I got ahold of him and asked if he’d be interested in my mailing him a copy (especially since I’d dedicated the book to him). Instead, he invited me to lunch so we could catch up. Well, who was I to pass up a free meal?

Mike was in fine spirits that day, complimenting me on the book and remembering the potential the property still has for ancillary development. It was a fantastic two-and-a-half hour get-together as we talked about old times and the projects we were currently involved with, and as we left the restaurant he shook my hand and wished me continued success.

Like I said, Mike was an easily likeable guy, attentive, encouraging, and a firm believer in letting creative people be creative, and I’m glad I was able to know him, and to be encouraged by him.

Rest in peace, Mike.